Media change – today and then

Access and distribution

The access to books was difficult at first: literacy among the population was only between 5 % (countryside) and 15 % (cities) around 1500. It was reserved for the ecclesiastical and secular upper classes. Nevertheless, thanks to falling prices, knowledge and education increasingly reached broader sections of the population. The technological and economic development of printing laid the foundation for the Reformation that began in the 16th century. The publication of texts in vernacular languages and no longer exclusively in Latin as early as the 15th century contributed to this as well.

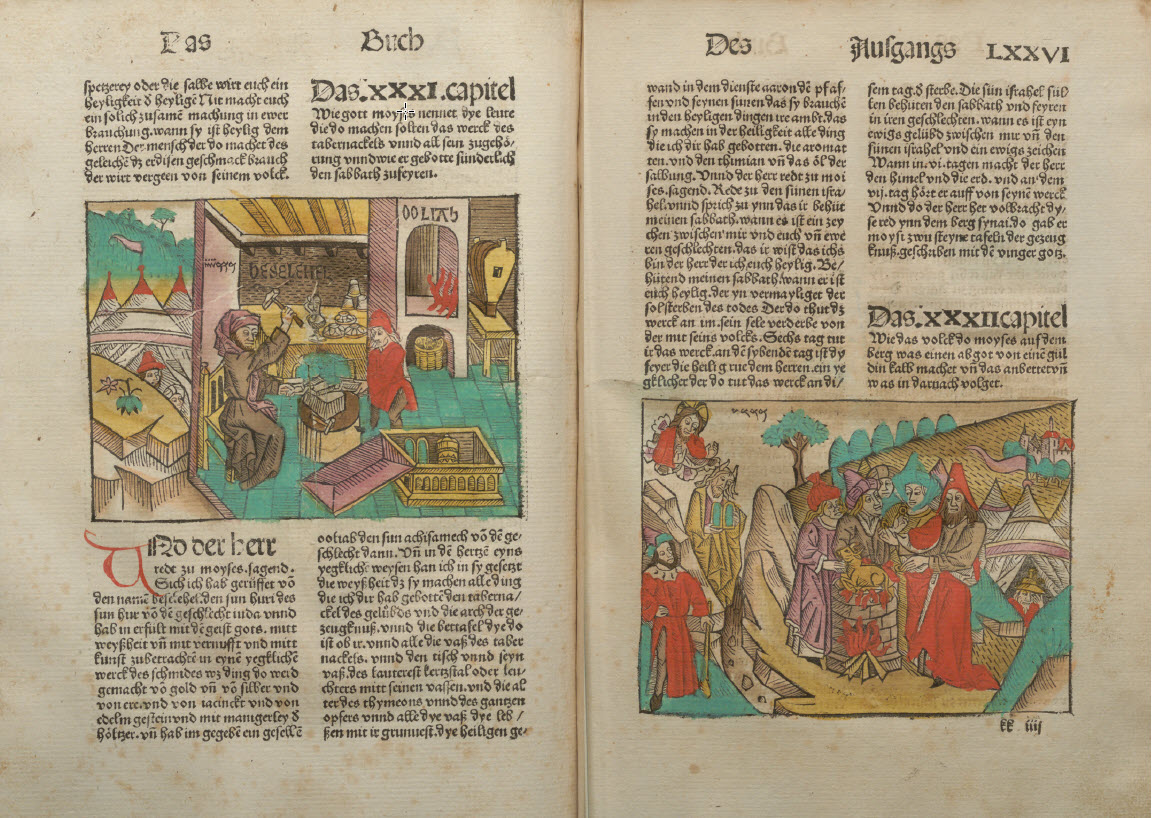

The need of the emerging bourgeoisie for an understanding of Bible texts led to the printing of German-language Bibles as early as the 1460s. They could be sold even better with illustrations. In 1485, Johann Grüninger in Strasbourg was the first to fulfill the desire for personal Bible reading with an edition in a handy format (height 29 cm).

Text and knowledge transfer

Thanks to the internet, we now have access to all kinds of books and writings around the globe within seconds. Already in the Middle Ages, there were texts with centuries of tradition. A single handwritten copy, however, often took years. Due to their small number, only a few people had access to the works - they were "password-protected", so to speak. Printed books, on the other hand, offered greater security for the preservation of the texts and came into circulation more frequently due to a higher number of identical copies.

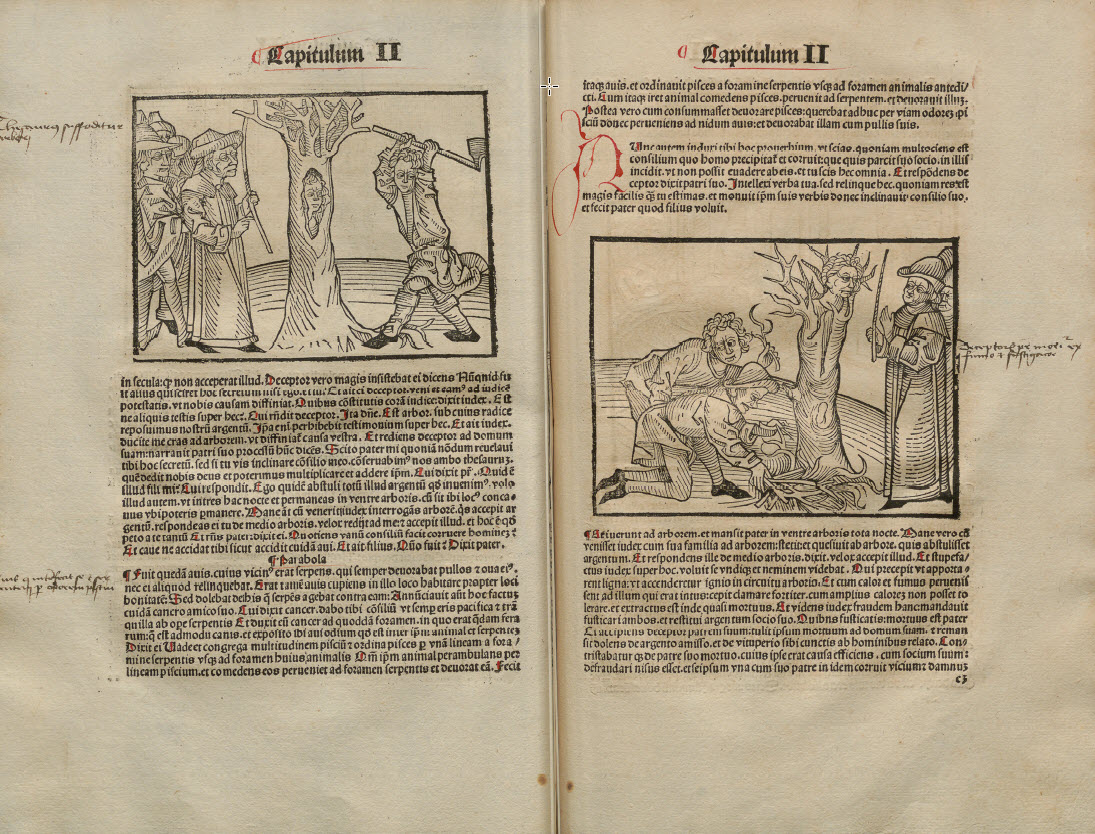

The originally ancient Indian poetry Panchatantra was written around the third century A.D. The collection of fables with moralising teachings served to educate young rulers (Mirrors for princes) and was translated into Middle Persian in the 6th century and into Arabic in the 8th century. In the 13th century, the Jewish author John of Capua, who had converted to Christianity, translated the work from Hebrew into Latin.

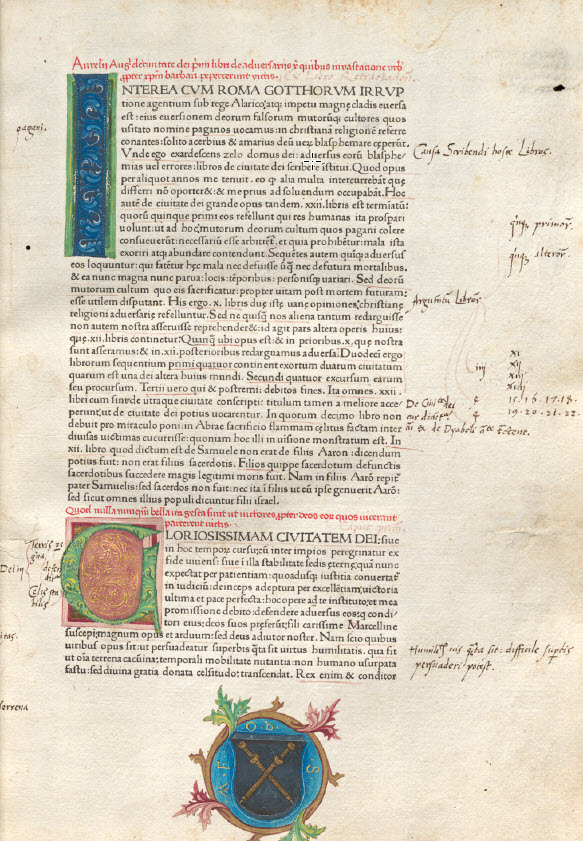

Scholars edited works by ancient and medieval authors from existing sources and commented on them. The typographically separated commentary often framed the original text. In this way, an intertextual network of knowledge was created, just as source editions are linked to further information through Linked Open Data in the Digital Humanities today.

Intellectual property and Copyright

Intellectual property and copyright as we understand it today did not yet exist. Many authors of printed works had died long ago. Contemporary authors even profited from reprints, as their works were thus distributed further. The first printers were the ones to suffer.

In order to prevent business-damaging practices such as the reprinting or pirating of a work by competitors, printers could obtain a so-called privilege from the local authorities. However, this did not protect intellectual property, but only material printing in their territory and was limited to a short period of time. The council of Venice granted the oldest known printer’s privilege to the printer Johann von Speyer.

Church and censorship

The church initially positioned itself with a certain reticence towards the new possibility for the multiplication of knowledge. It feared the spread of heretical ideas and their harmful effect on "uneducated and naïve laymen" who might henceforth consider themselves smarter than the priests. In 1485, the Archbishop of Mainz, Berthold von Henneberg, issued a censorship decree prohibiting the translation of Latin and Greek writings into German and their distribution and sale in his territory.

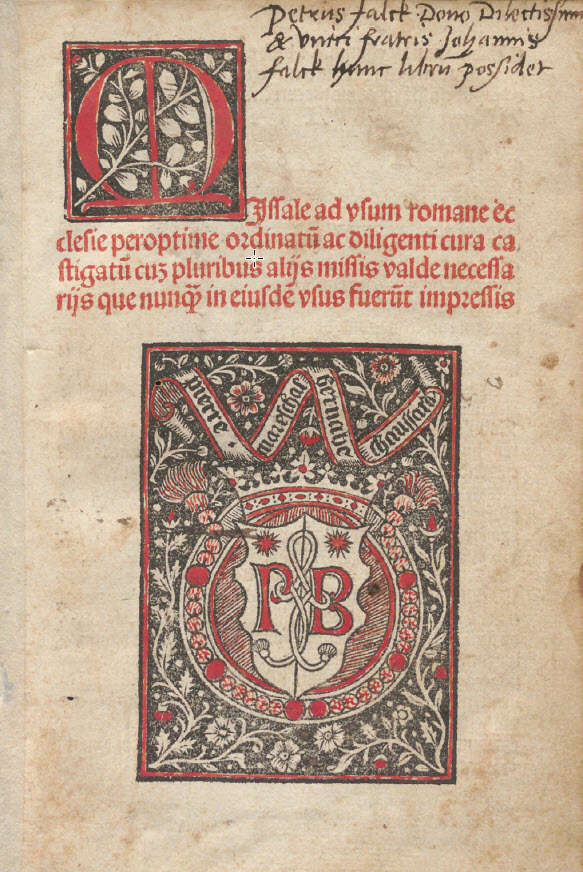

Soon, however, the church also took advantage of the new achievement. Until 1475, the most important printing towns were mainly bishop's residences, where Bibles and missals as well as indulgence forms were printed in very large editions.